The disease is terrifying. Many of the stricken are left in the streets to die horrible deaths, their bodies unclaimed. Thousands flee. The government appears helpless to stop the scourge from spreading. Physicians and nurses offer care, but have no effective methods of treatment or means to prevent the disease.

Ebola in West Africa? No, yellow fever in the United States. Both are hemorrhagic fevers.

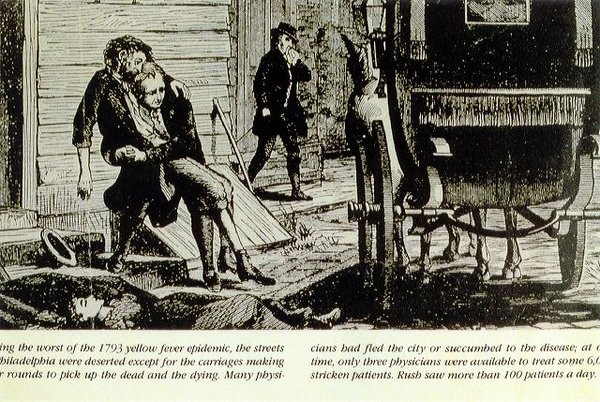

For centuries, yellow fever appeared in the U.S., spreading from port cities and coming most often to the American south. The epidemic of 1793 in Philadelphia claimed an estimated 4,000 lives between Aug. 1 and Nov. 9 alone, with thousands more deaths in the years that followed. “The Great Fever,” a documentary that is available in many public libraries, tells the history of this disease and its conquest. There is still no cure for yellow fever, which is endemic is some parts of the world, but there is a vaccine and we now know how the disease is spread—by the Aedes Aegypti mosquito, which also carriesdengue and chinkungunya, first seen in the Americas only last year.

Physician-historian Margaret Humphreys, one of the experts who appears in the film, teaches the history of medicine at Duke University in Durham, N.C., and has published on the history of yellow fever and malaria in the U.S., and on medicine during the Civil War. I interviewed Dr. Humphreys about yellow fever in the United States back then—and about Ebola today:

Yellow fever outbreaks always created panic. While physicians debated whether the disease was contagious, the people voted with their feet. Yellow fever causes a dramatic, painful, messy death, with patients screaming in agony and vomiting blood. Physicians had little to offer and were themselves terrified of infection. Such terror shut down communities, including all commerce and most jobs, leaving the poor even more destitute than usual.

What were the consequences of these outbreaks?

Short term, the epidemics of yellow fever in the United States caused thousands of deaths. The commercial impact was even more severe, because fear of the disease blocked trade in places where the virus failed to penetrate. The horrible events forced government response, leading to the funding of a state board of health in Louisiana, the first such entity in the country, in 1859. After the particularly damaging yellow fever outbreak in 1878, Congress created the National Board of Health, the first federal public health agency. It was housed in the Treasury Department, as its duties involved regulating interstate commerce (and stopping the entrance and flow of disease). It survived only a few years but in the late 1880s the fledgling U.S. Public Health Service emerged from the yellow fever outbreak of 1888, and proved its worth in the 1905 outbreak in New Orleans.

What parallels do you see between yellow fever epidemics of the past and the Ebola epidemic today?

I heard a report on NPR about the impact of Ebola on the economies of the countries most affected (Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea). Liberian workers usually cross the border into the Ivory Coast to harvest cocoa at this time of year, but that border is sealed to prevent the importation of Ebola. Commercial enterprises within the affected countries are taking a hit that may take years to rebound from. For these very poor countries, as in the 19th century American South, poverty in turn breeds disease. Malaria control has been set back, for example, as unpaid workers can’t afford medication.

Other parallels are tragically obvious—this is a horrible disease, with a high death rate, and its contagiousness seems obvious to caregivers. The choice of abandoning loved ones, and of abandoning the usual death rituals to avoid contagion, must be tearing families apart. I have also heard reports of people blaming the foreign doctors and aid workers who are there to help, claiming that they are in fact a cause of the outbreak. In 1905 New Orleans, when public health workers were treating the neighborhood cisterns to prevent mosquito breeding, Italian immigrants were sure they were poisoning the water, and attacked the water treatment teams. When a disease is this deadly, and the population affected is interacting with medical personnel who hold a different world view on disease causation, such frightening and heartbreaking scenes are likely.

Read more about The Public's Health.